Do your knees feel like they want to explode every time you squat to parallel? Do your joints scream at you every time you do a lunge? How about a jump? If you cringe at the thought of any of these, fear not because you are not resigned to only lifting upper body. Unless you want to be all upper body, which in that case, by all means do that, but be forewarned that doing so will leave you unbalanced.

Ideally, your knees should be able to flex and extend pain free throughout a full range of motion when you squat. Unfortunately, this is not the case for many people, and as a result, a lot of lifters become complacent with the fact that they have the poor knees. Fortunately, there are many ways to address knee pain and restore function, and in this article we are going to take a step by step approach to fix your achey knees.

Step 1: Look at Your Exercise Programming

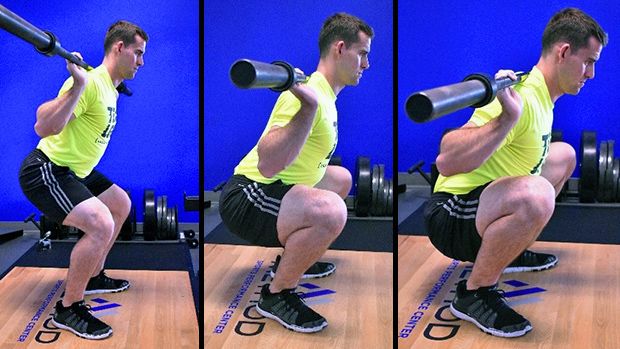

In order to master a movement like the squat, you need to squat often. I know at first that probably sounds like the worst thing in the world, but trust us when we say that you should be doing some variation of the squat 2-3 times per week. This could be in the form of a back squat, front squat, split squat, goblet squat, or any other variation you can think of.

Constantly varying your squatting movements will keep you from overtraining one particular version of the squat. To give an example of this, let’s take a look at the back squat vs. the front squat. Both are great ways to squat, but the emphasis of the movement is different for each squat. Your hips are more active in the back squat in comparison to the front squat. Your quads on the other hand will be more dominant in the front squat in comparison to the back squat. We could get into the physics of this and discuss moment arms and levers, but we don’t want to work that hard to explain it. For our purposes here, just know that you need to change up your squat often.

It is important to note that a squat is considered a knee dominant movement. In order to balance out your squat, you will need to perform hip dominant (hip hinge) movements as well. You should be doing hip hinge variations 2-3 times per week. The hip hinge can take the form of a deadlift, trap bar deadlift, kettlebell swing, good morning, or any variation you can think of. Hip hinge movements are great at working the glutes. These strong glutes will keep your knees from caving (preventing injury) and will help you sit back in your heels as you squat.

In addition to adding more squatting and hip hinges to your program, another aspect you need to look at is the amount of plyometrics you are performing. When we jump, gravity is pulling us down with a force that is 1.5 – 3x greater than our body weight. That’s a lot of impact for anyone. The impact from landing takes a great toll on our joints, especially if proper landing mechanics are not applied.

Although we would never say that you shouldn’t include jumps into your training program, knowing when to apply them will be of great value in order to increase your strength and prevent injury. Do NOT perform endless repetitions of plyometrics as a conditioning tool at the end of your workout. You will be tired at the end of your workout, and your landing form is going to pay the price. This only increases the vulnerability of your knees. There are plenty of other exciting exercises you can perform to condition your body at the end of a training session that won’t leave you with scabby shins and achy knees.

DO use plyometrics as tool to activate your nervous system before you strength train. Performing a whole body movement such as a jump that requires the muscles to contract quickly is a great way to prepare your nervous system to lift heavy weights.

Step 2: Revisit Your Technique

Once you’ve gotten your exercise programming together, it’s time to take a look at your technique…

About the Author

A Powerlifter from 1994 -1998, he has also won 2 National Powerlifting Championships, 1 World Championship, and holds 4 American Records and 3 World Records. Chad joined the Master Trainer program in the winter of 2014 and takes great pride in helping educate the future coaches of the franchise.